From Pruszków to Ravensbrück

11.08.2020

ehemaliges Durchgangslagers "Dulag 121" Pruszków, Foto: B. Piotrowska

On August 1, 1944, the Polish underground army "Armia Krajowa" began an open fight against the German occupier in Warsaw. The unequal fight lasted a total of 63 days. When the uprising collapsed and there was no chance of its successful ending, the commander-in-chief of the Home Army, General. Kazimierz Iranek-Osmecki signed the conditions of surrender on October 2, 1944, which General Tadeusz Komorowski announced on October 3. During these 63 days, between 130,000 and 180,000 civilians lost their lives.

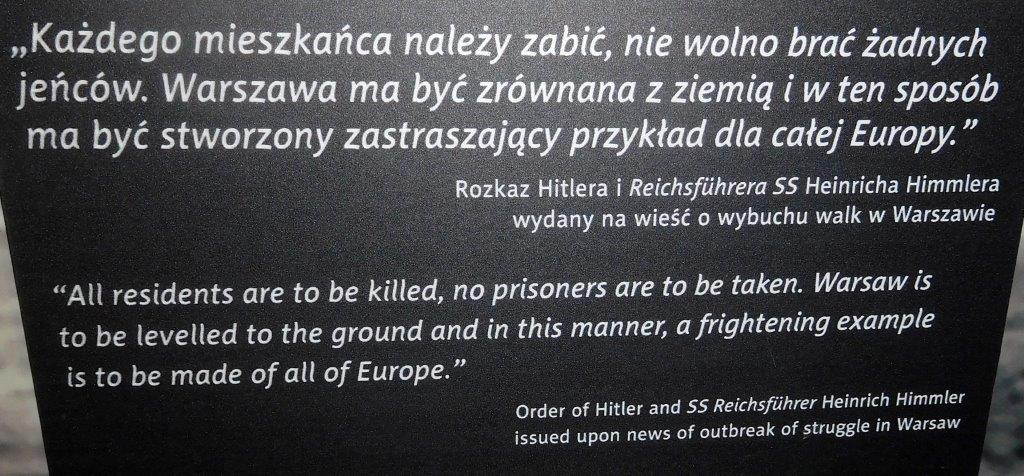

The exodus from Warsaw began. The Germans had a plan to completely destroy Warsaw.

Apart from the Wehrmacht, the units of the SS RONA Brigade and the 36th SS Division Dirlewanger were also involved, known for their brutality and responsible for massacres of civilians in Wola, Ochota and Powisle. People who were still in the city were brutally thrown out of cellars and apartments and taken to transit camps in Pruszkow, Ursus and Piastow. They often left their homes without food, warm clothes or kitchen utensils. It was accompanied by robberies, rapes, murders and arson attacks by the Germans.

The railway workshops in Pruszkow near Warsaw were used as Durchgangslager (Dulag) 121. From there, thousands of people able to work were sent to the Third Reich.

The worst fate befell those who ended up in concentration camps. Transports departed from Pruszkow to Buchenwald, Mauthausen, Stutthof, Auschwitz, Sachsenhausen, Oranienburg, Ravensbrück, Gross-Rosen, Neuengamme, Flossenbürg and Dachau. During the operation of the Dulag 121 camp, about 60,000 prisoners were sent there, most of them lost their lives.

Many tens of thousands of civilians were deported to concentration camps or for foreign and forced labor in Germany.

From mid-August to early October 1944, 12,000 women were transported from the devastated Warsaw to Ravensbrück. Many of them with children.

Among them was nine-year-old Barbara Piotrowska, now a member of IRK, who was deported with her mother, Marta Stachowicz, from the transit camp (Dulag) 121 in Pruszków to Ravensbrück.

Barbara Piotrowska recalls: “Our freight train with carriages without a roof stopped at night. It was dark, but the terrible spotlight terrified me. Men with dogs were waiting for us and we had to jump out of the carriages. I was nine years old and in this situation I was terrified. We all had to run to the big tent. The tent was crowded but my mom found some space for us on one side. It was a huge mess and we lost contact with our neighbors from Warsaw. The whole time I was worried about losing my mother in this crowd. "

Source: Memoirs of Barbara Piotrowska, IRK member, March 2020

After the Warsaw Uprising, 21-year-old Alicja Kubecka was arrested and transferred to Pruszków, and a day later deported to Ravensbrück.

“On September 3, we, men and women were crammed into cattle cars. (…) After a few hours, the train stopped (in Wroclaw) and the doors were closed. People on the platform, mainly Germans, started giving us bread, tomatoes and water. But it didn't take long as the Nazi escorting us had slammed the doors and the train continued on. (...) The next day (after a one-day stay in the Groß-Rosen concentration camp near Wroclaw), the women were taken to another railway station and placed in cattle cars. This trip took much longer. (...) The train stopped for a long time several times, but the doors were not opened. First of all, we lacked water, some of us still had something to eat and shared it. In exhaustion we have reached our destination: Ravensbrück ”.

*Source: Karolin Steinke, “Trains to Ravensbrück. Transports of the Reichsbahn 1939-1945 ”, p. 87, Metropol Verlag Berlin, 2009; ISBN 978-3-940938-27-5. *

The mother and grandmother of Hanna Nowakowska, the current vice-president of IRK, Janina Ciszewska and Władysława Buszkowska, were also deported to Ravensbrück after the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising.

Janina Ciszewska, then 22, recalls: “Germans threatened to throw grenades into the basement where our mother and I lived so far; the building itself had been bombed before. We went to the church of St. Jacek, where the insurgent hospital was located, we spent about two weeks there. The Germans threatened to bomb the church if we didn't surrender. One of the men came out with a white flag and we left the church. The Germans rushed us towards Wola. Then we were deported to Pruszkow. From there we were transported to the Ravensbrück camp in cattle cars. From time to time we had breaks and the Red Cross people gave us water, and sometimes a piece of bread. ... When we arrived in Ravensbrück, we were put in some kind of tent without a top. Everything was dirty and infested. We spent the whole week there. Then they took us to the bathhouse, where they shaved us, and then drove us outside. They kept us in the yard without clothes for two days. And it was already cold because we arrived at the end of August. Then they gave us clothes, various dresses with crosses sewn on the backs because there were no more striped uniforms and striped caps on the heads. "

Stanisława Tkaczyk, 17 years old at the time, said: “We got married in one of the Warsaw cellar - this is how insurgent weddings were held. We did not know if and how long we would survive. We were threatened with death every hour and we wanted to be together. (...) We were young, in love - it was our first love. (...) … We all fought, all civilians. We organized food for the elderly and dug trenches. Our house was completely burnt down, we escaped to another building and stayed there in the basement for two months. There was no water. We had to cross the street, go for water, but the street was shot at by Germans. That is why, we young people have dug a tunnel, deep tunnels. We also built a wall of dug earth so it was impossible to see us as we passed. When we left Warsaw, we literally had to walk over the corpses (...) We came to a transit camp in Pruszkow. I remember people were calling out, looking for themselves in the crowd. People were transported from Pruszkow to camps. (...) We were transported from Pruszkow in cattle wagons, incredibly crowded. It was impossible to attend to your physiological needs. The train was surrounded by an escort with machine guns ready to fire. Only after a few days, a stop was ordered and we were allowed to leave the wagons for a while. They treated us worse than animals. We didn't know where we were going. They told us we were going to work. When we got there, it turned out to be a concentration camp. We all cried and groaned. And what kind of welcome did we have - a line of Aufseherinnen and guards with rifles and huge dogs. We were chilled to the core, panicked, didn't know what to do. One of the women told us: "This is a concentration camp, we won't leave from here." Horror - we were young, beautiful and healthy".

The "Dulag 121 Museum" in Pruszków near Warsaw, established in 2011, has an archive containing oral and written reports from the Warsaw "Durchgangslager 121"