Exhibition opening

26.12.2024

Thanks to the Grini Museum for allowing me to represent the descendants of the female prisoners at Grini during the opening of this important exhibition, which highlights their stories. My mother, Karin Eidsvold, born in Oslo in 1918, was arrested in May 1942 along with her husband, my father, for their active role in the communist resistance movement. Karin’s parents and sister were also arrested on the same day. As a courier and distributor of illegal newspapers, she took great risks. Both of our parents were held in German Nazist captivity until the end of the war. Karin spent one year at Grini, where she was considered a dangerous prisoner due to her serious political background. She spent six months in solitary confinement, a horrible time that left her with a lifelong fear of small, enclosed spaces. She organized a system for passing information to those about to undergo interrogation, through small bundles tied to the outside of the cell windows, which saved the lives of named individuals. In June 1943, she was sent on the boat Monte Rosa to Germany, where the female prisoners ended up in the Ravensbrück concentration camp. The uncertainty of what awaited them soon turned into a brutal reality. Ravensbrück was a slave labor camp for female prisoners, where they were forced to work for German industry. Karin worked as a cutter in a textile factory producing military uniforms, operating dangerous machines, and enduring 12-hour workdays, six days a week. They were subjected to daily roll calls in all weather conditions, under strict surveillance—an immense strain. German prisoners led an underground organization in the camp and infiltrated the administration. When Karin was sentenced to 25 lashes for organizing fabric scraps for a sick fellow prisoner, a German inmate managed to have the sentence erased before it was carried out. The Norwegian prisoners were a small group within the camp. They shared their meager resources with one another and kept track of the Norwegian "Nacht und Nebel" prisoners. Correspondence home was strictly censored, but Karin received secret letters from her mother and sister hidden in food packages, which she kept—and which I still have today. The Norwegian women at Ravensbrück were in a unique position. They received parcels with food and clothes, including Red Cross packages. Karin "adopted" a young Yugoslav girl, sharing her packages with her. "We didn’t starve," Karin said, "but we froze." The stories of the female prisoners have been told far less than those of the men, even though the women also fought against the occupation and experienced the brutality of captivity firsthand. And as women, they were particularly vulnerable. Kristian Ottosen writes in his book: "The brutality of everyday life in Ravensbrück must have surpassed most of what the Norwegian male prisoners in Germany endured." In April 1945, Karin and the other Norwegian prisoners were liberated by the White Buses. The International Ravensbrück Committee (IRC) was founded by former prisoners, with children and grandchildren continuing to preserve the memory of the women's suffering and resistance. Today, I am a Norwegian member of the IRC, along with Bente Børsum. Our work focuses on remembering the women's suffering and courage, and reminding today’s generations of the necessity to fight against war, fascism, and racism. This work is challenging today, but all the more important. From this year’s IRC conference in Terezin, Czech Republic, I bring gratitude and best wishes to the Grini Museum for this exhibition that focuses on the female prisoners. Over the years, my mother told me about her experiences, both at Grini and Ravensbrück, and I have written down everything she shared. For our parents, the most important thing after the war was to resume their lives together, get back to work, and continue their political activism. They suffered health issues as a result of their captivity, and it wasn’t until later that we realized we had grown up with two traumatized parents. We came to understand how difficult it must have been for my mother to live with pain, fear, and mistrust after all she had endured. Karin Eidsvold passed away in 1984 at the age of 66. She was politically active throughout her life, with a strong will to fight against war, fascism, and for women’s rights. Her last effort was distributing brochures against nuclear weapons—"she died with her boots on." Women like her were not portrayed as heroes after the war, and those who fought in the communist resistance movement received no recognition either. Many, including my mother, were politically monitored for years. I was also under surveillance from the age of 9. My brother and I remember our mother with gratitude for the legacy she gave us: the struggle for women’s rights, peace work, and a firm stand against fascism and racism—a legacy that has been and continues to be a valuable foundation in our own lives.

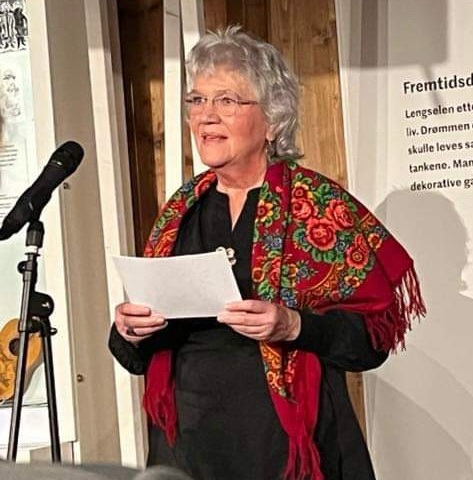

Tone Eidsvold